Article about ArtPeers and collaborators continuing the transformation of a neglected urban parking lot, Artpeers— creating public art performances of contemporary dance one night and original hip hop the next, capturing them on film. The resulting films will go on to premieres this fall. But first, this August 17, a sneak peek compilation of the two films will be screened at Movies on Monroe, in the very spot they were created.

Written by Holly Bechiri

1: urban parking lot.

1: director.

6: videographers.

5: dancers.

2: musicians.

2: computers.

1: keyboard.

1: teeny tiny baby keyboard I’m told is called a MIDI, all caps.

Oh, and:

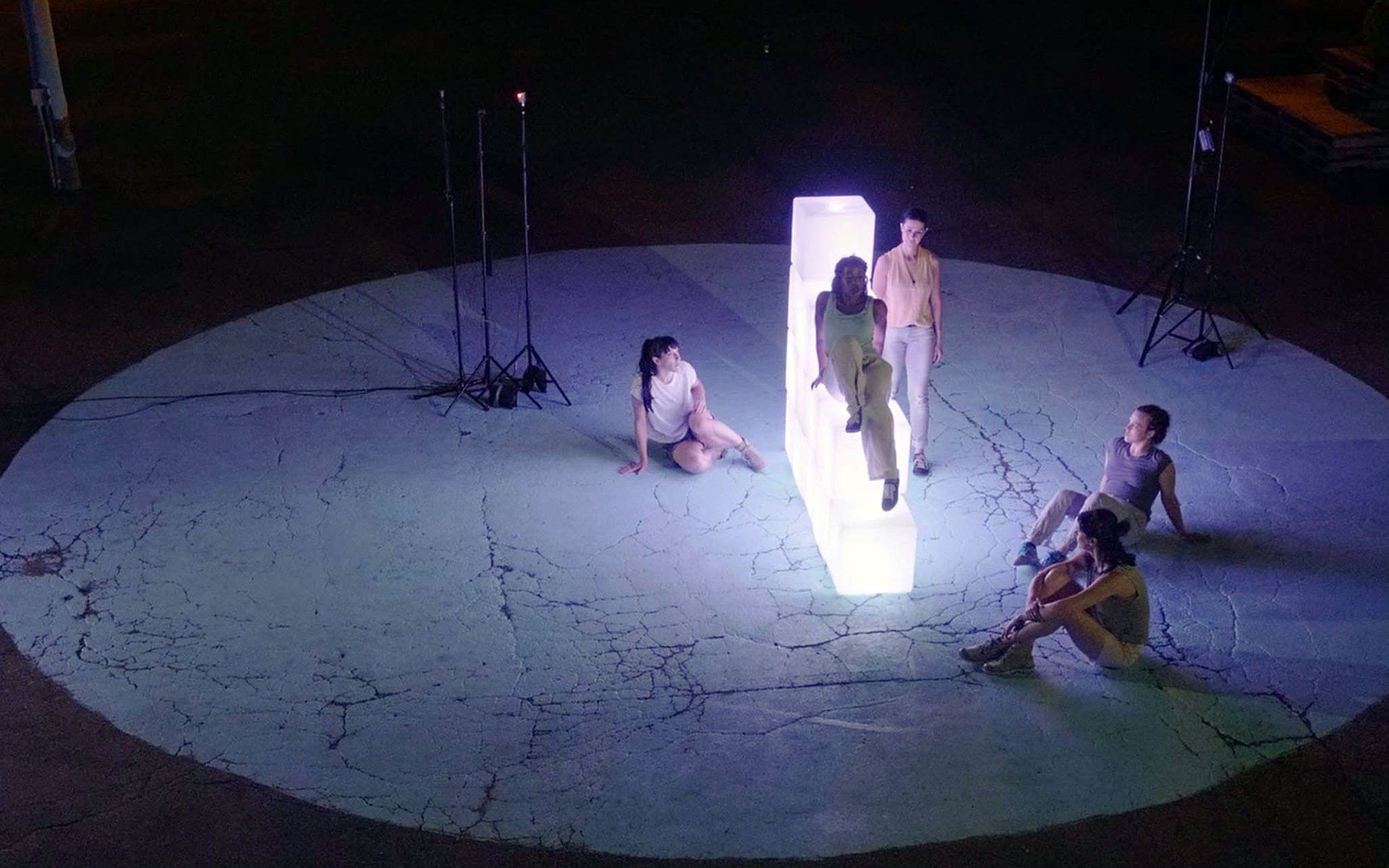

24: frost-white cubes that light up and don’t respond to music, but rather create it, based on their position in space.

On a buggy summer night in a formerly run-down parking lot just north of downtown Grand Rapids, the above tally of elements were brought together. They were built on long-standing relationships of trust, on a belief in what’s possible in public spaces, and a value for the diversity of talent needed to transform our assumptions and show us, like a whisper growing into a roar:

On a buggy summer night in a formerly run-down parking lot just north of downtown Grand Rapids, the above tally of elements were brought together. They were built on long-standing relationships of trust, on a belief in what’s possible in public spaces, and a value for the diversity of talent needed to transform our assumptions and show us, like a whisper growing into a roar:

“Here’s what’s possible: beauty.”

For four hours, I stood in that North Monroe parking lot, mesmerized, watching the moments get captured on film, just experiencing the very middle of a long creation process spanning months and years, as the second night of site-responsive public art performance is captured on film.

The highly collaborative project includes local talent from ArtPeers, DITA, The Grand Rapids HipHop Coalition, SideCar Studios, and East Coast talent in Masary Studios, is a result of many more collaborators needed to make it possible before the performance could even happen: the City of Grand Rapids, including its Parks Department, who owns the parking lot, the Downtown Grand Rapids Inc. (DGRI) organization who is bringing that parking lot back to life with movies, murals and streamers and yarn bombs, and all kinds of activation.

“We invested time, energy, and resource to transform the riverfront location of the ArtPeers shoot from a gritty parking lot to a clean and inviting pop up park,” says Andy Guy, Chief Outcomes Officer at DGRI. “We’re eager to see the community take ownership of this location as a new public space, and we’re grateful that ArtPeers took an interest in the site. This unique production helps expand our collective imagination about what can happen in the future.”

Along with DGRI, local arts-championing Wege Foundation and Goodrich Quality Theatres provided the financial and technical backbone needed to make quality work possible. The list goes on.

Along with DGRI, local arts-championing Wege Foundation and Goodrich Quality Theatres provided the financial and technical backbone needed to make quality work possible. The list goes on.

It’s a complex collaboration with so many moving parts it’s hard to keep track of it all, or understand completely the massive level of orchestration, behind the scenes and leading up to two nights of filming to pull it off.

It all started as simply as an email, asking to work together.

Taking an email conversation to the orchestration of so many moving parts was possible thanks to years of building relationships, both between ArtPeers’ Erin Wilson and all of the collaborators and between the collaborative partners as well.

Great art, after all, is not made between strangers.

Wilson’s direction of dance on film, along with numerous other films, events, and creations have given him ample opportunities to learn to pull multiple pieces together and keep a vision intact.

His wife and long-time collaborator Amy Wilson, along with her dancers of DITA, was a leading collaborator the night of the dance on film. Though the DITA collaborative normally has months to practice their performances, this opportunity required a quick turnaround. It put to the test a belief that their time dancing together, building a movement vocabulary over years would be enough for them to lean on, to flow into a responsive moment with the cubes.

“Aside from the fact that the cubes are just cool and I really wanted to get my hands on them, we thrive on collaboration and entanglements…and we love a good challenge,” laughs Amy Wilson. But then she gets serious, belying a curiosity and desire to learn that she’s built upon over years of opportunities, many of which she’s created herself. “Every project that I do is research for the next project.”

No surprise to those in the community that have followed this contemporary dance collaborative, some of them dancing together for nearly a decade under Amy Wilson’s skillful direction, that the research and years building up a shared movement vocabulary did in fact prove to be more than enough.

No surprise to those in the community that have followed this contemporary dance collaborative, some of them dancing together for nearly a decade under Amy Wilson’s skillful direction, that the research and years building up a shared movement vocabulary did in fact prove to be more than enough.

SideCar Studios is no stranger to capturing site-specific art performances on film in stunning ways. From each angle, ArtPeers has collected stunning local talent to pull off new visions for what is possible.

SideCar Studios is no stranger to capturing site-specific art performances on film in stunning ways. From each angle, ArtPeers has collected stunning local talent to pull off new visions for what is possible.

And then there are those 24 light boxes. Ryan Edwards, of Masary Studios in Boston, has created frost white plastic boxes, probably two feet wide on each side, with a computerized system in each one that enables it to be geolocated within a space, connected to computers and keyboards and programs. Think of it, explains Edwards, as notes on a staff, but instead of on paper, the staff is physical space, and as the cubes are moved around, the music they create is changed, affected by their location and the players interacting with them.

You may have seen lightboxes before, with an already-genius system of creating light that responds to music. This takes that step and flips it around a few times, adding complexity until them cubes themselves are the ones determining the music that’s created.

It took two musicians, two keyboards, two computers to interface with those programs and systems and set the cubes off on their music-making capacity—plus five dancers one night and as many young hip hop lyricists the other night to move them around and change their potential. Like the boxes themselves, designed to be responsive and interactive and collaborative, the collaborators themselves had to all work together, responsive and interactive with both the technology they were exploring and among themselves.

I watch the public art performance and its concurrent filming for multiple takes. Then they do it all again, slow to frenetic, “tight this time.”

The light boxes are built of science and technology, and people turn it into music, poetry, artistry.

Musicians, dancers, film artists, dreamers, and believers—all brought together to make magic happen.

The first night, Edwards and Wilson worked with the Grand Rapids HipHop Coalition, headed by Rodney Brown and Vic Williams, known as Gov. Slugwell. The Coalition infuses students with the history and skills of creating poetry in the form of hip hop, and had prepared them to perform their work the first night of filming with the cubes. They were just finishing up a week of summer camp with their students, full of lessons on the history of hip hop combined with skills building so that the students could create their own lyrics, all built around the theme of “the community I want to live in.”

The first night, Edwards and Wilson worked with the Grand Rapids HipHop Coalition, headed by Rodney Brown and Vic Williams, known as Gov. Slugwell. The Coalition infuses students with the history and skills of creating poetry in the form of hip hop, and had prepared them to perform their work the first night of filming with the cubes. They were just finishing up a week of summer camp with their students, full of lessons on the history of hip hop combined with skills building so that the students could create their own lyrics, all built around the theme of “the community I want to live in.”

“People hear the word hip hop, and a lot of things form in their minds,” says Erin Wilson. “and it’s really constrictive to what the potential is for that art form. So it felt like turning canon on its head to have these soft white lights that changed colors in the middle of this parking lot that has fish painted on it and then—of course—we have 12-year-old kids performing their original poetry. We want to present these narrowly-defined genres in ways that contradict the narrow definitions.”

Brown and the entire Grand Rapids Hip Hop Coalition is working to upend those assumptions, whether they’re about hip hop, about urban spaces, or about the potential of Black talent. They do that through their work in the Coalition, such as the summer camp that combined lessons on African history, entrepreneurial skills, and musical theory. But they also do the work through collaborations such as this one with ArtPeers.

“If there’s a greater willingness to be inclusive at the onset, then the projects that are being proffered out in our community wouldn’t lose any value or any artistic integrity, we would be enhancers,” says Brown, pointing out that the more diverse contributors that are included, the more layers of flavor that can be reached in the end product. “It’s a missed opportunity to not be able to add that flavor.”

The students, like the dancers did the following night, start their performance by walking solemnly, through a multicolored streamer-lined entrance, with a light box in their arms. The symbolism of everyone coming in, all entering into a public space, all leading its activation as they make music and beauty and pronounce possibilities, is not lost on me.

The students, like the dancers did the following night, start their performance by walking solemnly, through a multicolored streamer-lined entrance, with a light box in their arms. The symbolism of everyone coming in, all entering into a public space, all leading its activation as they make music and beauty and pronounce possibilities, is not lost on me.

It is, after all, an important impetus for the entire project: what’s possible in public spaces? Is everyone welcome? What can happen here, in our community?

It is, after all, an important impetus for the entire project: what’s possible in public spaces? Is everyone welcome? What can happen here, in our community?

The answers—at least for this group of collaborators on these summer nights in what was once an abandoned, weed-filled parking lot—are that the anything you can dream up is possible, that yes more diversity of talent is not just welcome but necessary if we want the best our community can create, and beauty—beauty is what can happen here.

It all started with just an email, but like the music and the movement, the creation process for this work,spanning months and years, is a slow build that results in this complex symphony of light, sound, and movement.

The light boxes were first conceived four years ago. Dancers from DITA have been working together, building their movement language and collaborative skills for as much as a decade. Erin Wilson has been honing his orchestration skills, working with organizations and governmental agencies and artists, over much of his adult life.

“Erin has really created a space where everyone can explore…his vision was proven,” says Edwards, pointing out that an important part of everything working depended on Wilson preparing him to be open to new relationships and others interacting with his cubes. This didn’t come without building in time to get to know others, forming relationships of trust with those he was just meeting before they were expected to create the performance together.

The method—build not just projects but relationships—may be the most important element in the level of quality that ArtPeers has become known for and, Edwards says, has created again.

“[This collaborative project is] at the top of quality—on par with any high-end project I’ve ever been a part of,” he explains, making sure I know this isn’t just “best quality for a small city stuck in the Midwest” but best quality, anywhere, including the East Coast and even international opportunities he’s been involved in over the years.

Big words that are difficult to actually accomplish with integrity. But after experiencing the work and talking with half a dozen collaborators, it’s undeniable: what’s being created can only appropriately be called magic.

Big words that are difficult to actually accomplish with integrity. But after experiencing the work and talking with half a dozen collaborators, it’s undeniable: what’s being created can only appropriately be called magic.

There’s this idea that if you peek behind the curtain, you’ll lose the magic. Dorothy and her traveling friends were disappointed to find a small little man in need of grooming and, perhaps, better fashion sense.

There’s this idea that if you peek behind the curtain, you’ll lose the magic. Dorothy and her traveling friends were disappointed to find a small little man in need of grooming and, perhaps, better fashion sense.

But I got to peek behind the curtain, and what I found were layers and layers of magic—in the making, in the mechanisms, in the meaning.

“When you bring those diverse talents to the table, you can create magic. We want to create magic—art that inspires,” says Brown. “If we want to see the magic, we have to be intentional about co-creating spaces.”

I didn’t lose the magic—I got swept up in it.

See the premiere of the compilation video:

Movies on Monroe – Wonder Woman & Black Panther

555 North Monroe

6:30 p.m.

Friday, August 17

Admission is free and open to all.

Collaborative partners for the cube project include:

Collaborative partners for the cube project include:

ArtPeers SR|XD

DITA

Downtown Grand Rapids Inc. (DGRI)

Masary Studios

SideCar Studios

Hip Hop Summer Camp Experience

The Grand Rapids Hip Hop Coalition

The Love Movement, Inc.

The Hip Hop Literacy Project

Wege Foundation

Goodrich Quality Theatres Inc.

The City of Grand Rapids

City of Grand Rapids Parks and Recreation Department

City of Grand Rapids Office of Special Events